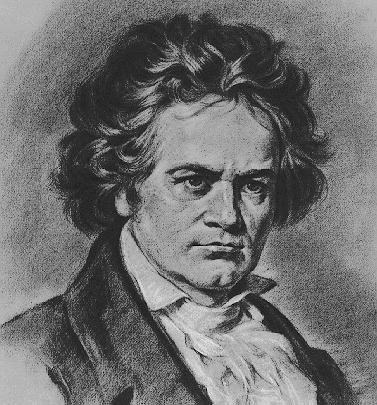

| THE NINTH |

22nd July 2001

|

|

I am sitting in the dark listening once more to the sheer

magic and genius of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, the world's greatest

music. This symphony is God's plenty. The Fifth Symphony, in contrast,

is perfect order-every hair in place, nails trimmed and clean, shoes

polished. It is tidy. Not so the Ninth. It spills over, slops around,

sloshes out of its container. It has symphonic music, church music,

military music, life and death, the oppositions in all things, Yin and

Yang, the universe-and a whole array of popular tunes. That's one thing

I love about Beethoven-he always gives you a few catchy melodies to

hum as you leave the concert hall. I unabashedly confess to being a Beethoven junkie. I started as a kid. Ever since I learned to play the Minuet in G and the Moonlight Sonata as a young piano student, Beethoven has had me in his thrall. I never heard any of his music that I didn't like. I have slogged through typhoons to get to concerts where they were playing his stuff. I have endured scratchy recordings and bad performances just to feed my habit. And the music is ever new. There is always something to discover, something you didn't catch before. The first time I heard the Ninth, I wept through most of it. It is said that the first audience ever to hear it stood during the military march. The astonishing fact is that Beethoven was stone deaf when he composed it. He personally conducted the debut performance, and when it was over, he slumped exhausted on the conductor' podium. One of the orchestra members-perhaps the concert master-turned him around to SEE the thunderous applause of the standing audience. Here lies the awesome mystery: How can anybody, deaf or not, write such music at all? But especially how can a deaf person do it? I stand in reverence of such genius. I can't understand it, any more than I can understand what the Ninth is all about. I can only revel in it. The fourth movement's quartet, like its choral conclusion, was considered impossible to sing by the original performers. The soprano went to Beethoven to complain, to bitch actually, to talk him into lowering a few of the high notes, to make it easier. He gruffly refused, whereupon the lady said, "Then we must learn to sing it-for God's sake." Beethoven was a gruff man-a bitch. His life was troubled, irregular, unhappy. The romanticized movie portraits of him-Disney's many years ago, Gary Oldman's more recently-are not very accurate. They tried to clean him up, soften him. He wasn't soft or clean. But we forgive him because one thing is happily sure-he gave away his life to ensure that one note followed another inevitably. Of all the composers, Beethoven's is the greatest soul. Mozart was a technical whiz, Tchaikovsky wrote gorgeous melodies, Chopin was the poet of the piano. But Beethoven's music changes you even as you listen. Beethoven has the power to break your heart. The heart of the Ninth is, to my mind, the third movement, Adagio molto e cantabile. In the old days before CDs, most recordings of the Ninth interrupted the third movement midway, and you had to turn the record over to continue! The third movement begins like many another adagio composed by Beethoven and others. It is sweet, pleasant music played mostly by the strings, set in opposition to the loud and aggressive first and second movements. But then something happens that changes everything. Ever so gently, ever so subtly, some of the strings begin plucking in the background-the pizzicato. At first, they pluck just a note here, a note there-so gently you hardly notice. The violins, the violas and cellos-all take their turn. The horns, the flutes, and the drums come in for a few brief moments, then the strings take over again. But always in the back is the pizzicato, increasing with each phrase, now playing entire runs, now accentuating a note or a theme. It is music filled with such yearning, such joy and sorrow. When I first heard this, I felt as if the music were plucking at my heartstrings, plucking at my soul. Beethoven was tugging at my life. The experience was overwhelming. I can't really describe it-I can only ask you to hear it for yourself. Years ago, when my friend and colleague, Wes, was about to die of AIDS, I went to visit. I took a copy of the Ninth with me, at his request, because I had told him about the pizzicato as I have you. We sat together and listened to it. As the third movement played, he wept too. To hear this music, we found, is to be cleansed, redeemed, reclaimed, exalted. How did Beethoven know these things? The Japanese have an annual celebration of the Ninth, something like the way Americans revive Handel's "Messiah" every Christmas. It's a national party. I think Beethoven must be tickled pink knowing this. I'm not sure how he feels about all the tv commercials that use the Ninth to sell stuff, but maybe with the passage of time he has mellowed and will forgive them. The conclusion of the Ninth is, of course, Friedrich Schiller's great "Ode to Joy" set to Beethoven's music. What a collaboration! Somewhere, Schiller must be tickled pink, too. To hear it is to wish, as I have all my life, that you were a singer. O freunde, nicht diese tone¡K.. Not these sad notes! This is apt because the first two movements are loud and troubled, not joyous. So as the world can always use a little more joy, I commend the Ninth to anyone feeling down. Listen to it with someone you love, and LISTEN to it. Bob |